I have some thoughts on the Wicked movie

Archetype, cinematic realism, adaptation, color, theatrical stylism, and shooting for the edit

I. What is this feeling

Those who knew me in the seventh grade would be shocked to learn that I was not excited for the Wicked movie. 12-year-old Katie loved this show. It resonated with me in a way very few pieces of art had before, and I was not alone.

I can remember the breathless excitement of sitting in the theatre before the curtain rose and the habituated adrenaline rush that would accompany the mere mention of the show in my daily life. But the frantic energy with which I stood outside stage doors and belted the songs in the car is, I have found, irreplicable for me today, not only with regards to this show but in my life generally, and I don’t think this is a bad thing.

I received the confirmation of the long-anticipated Wicked film adaptation with curiosity rather than excitement, and when I watched the first trailer, I was entirely unimpressed. For a while, I didn’t even think I was going to go see the movie when it came out. The bizarre media tour, Cynthia Erivo’s fan poster drama, a few comments both Erivo and Grande made about the story, and the less than inspiring trailer made me not want to waste my time.

But let’s be real: I was never really going to avoid this movie. I’d spent a considerable part of my childhood obsessed with Wicked, and—home with my family over the holidays—I thought about what it was about the stage show that had so captivated me when I was younger. I retread the mental paths that I’d spent so much time on as a child, thought about the experience of going to see the stage show in different cities with my dad, and listened to the soundtrack for the first time in quite a while.

Anyway, I had a lot of thoughts, and though the storm of Wicked-related content is at a lull, here’s an unnecessary meditation on one of my favorite topics: artistic adaptation.

II. What are children and what is archetype

Even if you yourself weren’t a Wicked-obsessed tween in 2011, I think most of us who have been children will remember the feeling of being completely and utterly invested in a piece of art. A lot of kids my age felt that way about the Marvel movies, for example, or Harry Potter, or Percy Jackson.

I was in high school—and deeply involved in my school’s theatre department—when Hamilton first opened on Broadway. I have a vivid memory of hearing the announcement that we’d be doing In the Heights (an effort to engage with the Lin Manuel Miranda hype that was sweeping the nation); one girl, upon receiving this news in a room full of her classmates, screamed at the top of her lungs with joy and collapsed to the floor. Children are much more demonstrative than adults.

When we are young, we do not yet have the vocabulary or cognitive ability to explore our personhood effectively. We instinctively recognize the depth of our souls and that there is something to understand, but we haven’t yet cultivated the skills to contemplate it well. Much of our young life is a reaching for the means by which to express truths—about ourselves, about the world, and about life itself. As a result, we sometimes externalize and conflate our fledgling self-discovery with a piece of art.

Fantasy is an appealing genre for this type of internal work. Fantasy stories are explorations of extreme circumstances which bear resemblance to our world and lives, but which are worlds of magic and adventure. They are places to explore tragedy, triumph, morality, emotion, and what it means to be human—without having to confront these things head on in the real world. This is because fantasy deals in archetypes.

I don’t mean that fantasy can’t be nuanced. What I mean is that fantasy invokes archetypical characters, plots, and aesthetics and interrogates them via narrative.

Wicked the stage show relies very heavily on its score not only to convey emotional beats but to convince its audience to buy into its story. It simply isn’t meant to be an exhaustive exploration of the psychologies of its main characters or a comprehensive political analysis of Oz. We don’t have long dialogue sequences delving into the plot or characters. Wicked isn’t meant to be exhaustive; it’s a port of entry for its audience to engage with and consider the characters. In a word, it’s archetypical.

Wicked is an ideal landscape for this type of internal work; it is at its core a story about learning to properly see the other and oneself.

III. What is realism and what is color

The single biggest deterrent to my seeing this movie was the color grading, which many people have brought up in the (almost) year since its release. I genuinely wasn’t sure if I’d be able to get past it in the viewing experience.

Director Jon Chu has said that the decision to use such a muted color palette was rooted in a desire to “make Oz a real place,” and to make it so audiences could “feel the dirt” and “the wear and tear of it.”

I find this a bit sad. The claim that grit and desaturation are more real than clarity and color is such a pervasive lie in visual media.

Chu juxtaposes his desaturated color palette against the word “plastic.” What I think he really means by this is that he doesn’t want Oz to seem “fake,” but his use of the word is interesting.

“Plastic” carries with it modern, real-world associations. It’s something calculated, consumerist, disposable, modern, synthetic, artificial, superficial. It calls to mind Barbie dolls (and perhaps the best modern example of visual plasticity in film is 2023’s Barbie) and Vogue covers and teen girls’ “For You” pages. I understand the impulse to shy away from plasticity (in this sense of the word) if you’re making an effort to portray reality.

But color is not synonymous with plasticity, and Wicked’s great strength is particularly in its ability to show reality through archetype, through fairytale.

I want to compare Wicked’s color palette to a few other films, just to emphasize this point.

1) Into the Woods (2024)

Perhaps the best comparison in terms of content and goals is the 2014 adaptation of Into the Woods. Like Wicked, Into the Woods puts fairytales in conversation with reality, although the two have very different methods of doing so. Director Rob Marshall’s frame has depth that doesn’t detract from the piece’s interest in the grit of the story. It’s still less saturated than I’d like, but it doesn’t detract from my experience of the film. Not relevant to my point but as an interesting aside, like Wicked, Into the Woods (2014) is a film adaptation of only the first half of the stage show.

2) Les Miserables (2012)

Tom Hooper’s Les Miserables has relatively normal color grading. I bring up Les Mis for two reasons. First, it very quickly became the basis for the musical-adaptation-Oscar-bait film after its release, and second, it cemented the trend of “realism” in stage to screen adaptations (Hooper’s Les Mis deserves its own treatment, so I’ll leave this here for now).

3) I also want to highlight specific instances of grit (Shawshank Redemption, 1994), fairytale (Cinderella, 2015), and fairytale in conversation with reality (Big Fish, 2003), all of which make great use of color.

4) And I know Jon Chu can use color, because I’ve seen Crazy Rich Asians.

5) And perhaps this is unfair, but I wanted to showcase some stills from 2017’s La La Land to show what cinema can look like. La La Land should have had more of an impact on color trends in movie musicals than it did. It’s shot on 35mm in CinemaScope, with meticulous attention to the details of the colors, and it shows. Just look at how stunning the frames are. Look at how intentional the lighting is, at how warm and deep the world seems.

I don’t think that it’s fair to say that Wicked should have looked like, say, The Wizard of Oz.

Oz was shot in technicolor, and not only is that process expensive and time consuming, we also lack the technical ability to do it now. I also don’t think it’s fair to say that Wicked looks the way it does because Jon Chu or any of the production team lacks an artistic vision; what I’m critiquing here is not technical ability or lack of artistry, it’s a general rejection of color—of saturated Beauty—as real, as true.

So this brings us to our central question: is archetype—is fairytale—opposed to reality, or is it beyond reality?

I would propose that it’s the latter.

Wicked’s desaturated color palette doesn’t look more real; in fact, it looks less real.

Jon Chu’s Oz looks flat and two dimensional, and it really does impact the viewing experience. It’s also not helped by the decision to color Ariana Grande’s hair a shade of blonde that simply looks unnatural on her. She—and the world she exists in—look decidedly unreal.

The way that theatrical stylism conveys theme and atmosphere is very distinct from the way in which a film would convey those things.

Because Wicked 2024 functionally changes so little from its source material in terms of content and meaning, it gets a lot of leeway when it comes to its use of film language to convey these things appropriately. Conveying this type of archetypical stylism—which is integral not only to the atmosphere of Wicked’s Oz but also to its themes—in film is very tied to editing, shot composition, lighting, and, yes, color.

Sometimes, Wicked 2024 does this very well. Other times, it’s less successful. It feels a little strange to break a movie into chunks like this, but please accept this ranking of every musical number in Wicked 2024 (judged specifically as adaptations from the source material, not as songs in and of themselves):

Dancing Through Life: See below for my gushing review. No notes.

What is this Feeling: works for similar reasons to Dancing Through Life.

The Wizard and I: Erivo kills this song, and the blocking here (apart from the cliff finale) is pretty motivated which I appreciate.

Popular: Grande sounds awesome, the editing is a vibe, and it’s quite funny. Also, the color palette looks better here than in most of the film.

Dear Old Shiz: lots of interesting shots, and the choral harmonies are gorgeous.

Something Bad: frankly just not that memorable in either the stage show or the musical, but weirdly I like it better here than onstage

No One Mourns the Wicked: I don’t hate it. I think Grande sounds good. But it lacks the gravity that this number is supposed to have, and it’s shot oddly.

I’m Not That Girl: This one needs subpoints.

Erivo sounds awesome, but her version of I’m Not That Girl is subjectively not my favorite thing. I don’t feel like she retains the melodic integrity of the piece.

The blocking is very odd; Elphaba wandering through the forest feels strange and unmotivated, and cinematically it doesn’t do a great job of conveying her isolation.

But the main reason it’s ranked so low is because it represents one of the strangest (to me) changes in the script. In the stage show, “I’m Not That Girl” ends as it’s beginning to rain. Madame Morrible runs up to Elphaba, telling her that the Wizard has sent for her, hands her an umbrella—saying “Careful dear, mustn’t get wet”—and then magically makes the storm disappear.

This is important for two reasons: a) we see Elphaba get wet, so later when people are saying that water can melt her we already know that isn’t true, underscoring the manipulative rhetoric, b) we see that “weather is [Morrible’s] specialty,” and c) it underscores the idea that Elphaba hopes her loneliness and isolation will dissipate once she meets the Wizard.

In the film, I’m Not That Girl ends, and it is in the next scene that Elphaba gets invited to meet the Wizard (in broad, not-rainy daylight). It's about to rain, and Morrible clears away the impending storm. We lose all the above content except for (b).

One Short Day: interesting editing and well-performed, but while I love the Menzel-Chenoweth cameo idea, that new section of music doesn’t feel like it fits with the musical landscape of the rest of the soundtrack.

Defying Gravity: I know putting this one here is a hot take. Erivo’s vocals sound excellent, but the way this sequence is edited really damages the momentum of the song.

A Sentimental Man: I’ll be honest I simply find Jeff Goldblum’s Wizard very creepy and can’t look at him long enough to appreciate this song.

IV. What is a conclusion

In many ways, the Wicked movie is less a film in its own right and more a series of music videos. Some of them are amazing; some are okay; some aren’t good. This is not a net negative.

But in a world of book-to-movie/stage-to-movie adaptations, reboots, and franchised sequels, it’s important to consider what makes a good film in its own right. I don’t think that it’s too controversial of a statement to say that Wicked 2024 would have received nowhere near the level of attention and accolades that it did if it came out as an entirely original film today, without the backdrop of the musical’s success. Even if it was exactly the same final product.

And that’s okay.

Wicked 2024 is many things: musically and visually impressive, well-acted, a good story, a faithful rendition of the source material, funny, sad, beautiful, tragic, etc. But it is not cohesive as a film in particular.

All that said, I am excited to go see Part II! Perhaps I’ll have more thoughts then.

For more of my thoughts on adaptation as an art form, see my article on that topic here.

(BONUS) V. What’s the most swankified place in town

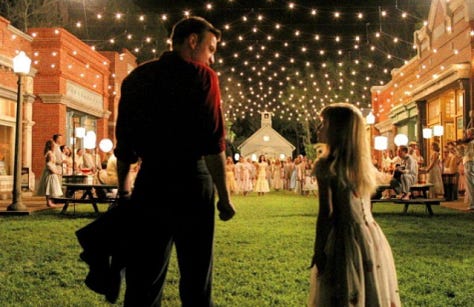

When Wicked 2024 works, it really works. There are whole sections of the film that are shining examples of near-perfect stage-to-screen adaptation. I had a fantastic time in the theatre. Exhilarating, even. And “Dancing Through Life” was far and away my favorite part of the film.

“Dancing Through Life” is a masterclass in adapting choreography from stage to screen. Choreographing a dance number for the stage is a very different thing from choreographing a dance number for a movie.

One of the differences is that on stage, the audience is viewing the whole stage and everything on it at once. They can choose to focus on a particular ensemble member, on one part of the stage, on the performance of the lead actor, etc. It is the responsibility of the choreographer (and the lighting designer, etc) to utilize the entire visual landscape both to communicate the story of the scene and to direct the audience’s attention to anything that is essential for the plot. They also need to consider throughout the entire number the way the stage looks as a whole.

In film, you as the choreographer/director/editor have direct control over where the audience’s eye goes at different points. This means that you can showcase particular dance steps, focus on facial responses in characters, and so much more. But it also means that you’re not simply choreographing a dance as a whole to be played out on a stage. You have to choreograph for the edit, and Christopher Scott delivers.

I’ve seen several people surprised at the film’s change to the dialogue interlude in “Dancing Through Life,” namely the decision to cut the line “What’s the most swankified place in town?”

I actually vastly prefer the film’s dialogue here. In the musical, Fiyero asks the students, effectively, “where do you all go to party?” Galinda tells him that they go to the Ozdust Ballroom, and Fiyero gets everyone to go party that night. In the film, Fiyero arrives already knowing about the Ozdust, an illegal club that Chu says showcases “the underbelly of Oz.” Particularly, it’s a club where animals gather. I love this change for two reasons:

It tells us a lot more about Fiyero’s character:

He's more explicitly a corrupting influence on his fellow students, encouraging them to do something illegal, but it also positions him as less encumbered by Oz’s political system.

Fiyero is more comfortable with the animals, so when he helps Elphaba rescue the lion cub later it fits with his character.

It also further distinguishes Winkie Country, where Fiyero is a prince, as a more tolerant refuge for the animals (this is also why Elphaba will fly west, toward Winkie Country, when she escapes the Emerald City at the end of Act I).

It emphasizes Elphaba’s social isolation: Galinda, in both the stage show and the film, tricks Elphaba into attending the party at the Ozdust. She invites her along and gives her what will become her iconic witch’s hat. Elphaba thinks that Galinda has done something genuinely nice for her and goes to the party, but it turns out to be a joke. Making the Ozdust this illegal club further emphasizes Elphaba’s desperate yearning to be accepted socially. That she’s willing to break the rules like this ups the stakes of the whole scene and makes the revelation that the invite was a joke much more devastating.

(I will say that this change also has one unintentionally weird byproduct. When Elphaba thinks that Galinda has reached out to her in friendship, she goes to Madame Morrible and tells her that Galinda must be let into the private sorcery seminar. It’s her way of reciprocating Galinda’s perceived offer of friendship. Elphaba says that Morrible must tell Galinda that very night, and in the stage show it’s funny that she shows up to this college party, drops off a wand, and leaves, but it’s very weird in the film that she fully goes to an illegal club, sees all her students there, and just drops off the wand and leaves. This is the result of the stage show being effectively adapted as a series of music videos rather than as an organic whole or as a narrative.)

I wanted to pay attention to this scene (and to “I’m Not that Girl” above) because it’s important to emphasize the impact of little decisions on the whole of a work of art.

Some decisions, of course, mean more than others. But there is a ripple effect to even the smallest choices. The little things build up to form themes and atmosphere. This is why it is not boring to rewatch a good movie, or to reread a good book.